A Tale of Paliochora

Author: George Koksma

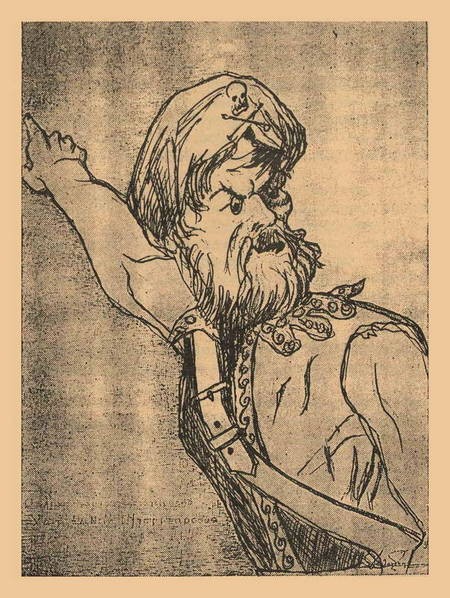

Illustrations by Dimitrios Zaglanikis

When Published: 2000

Publisher: Kytherian Society of California and the West

Available from:

Vikki Vrettos Fraioli

Price: $US3, plus postage

The ghosts may still be heard as you pass by Paliochora.

George Koksma has penned a poignant and harrowing tale of its destruction, coalesced from the lore he absorbed during his time on Kythera many years ago.

He is a Dutch engineer who was sent to Kythera by the World Council of Churches to help develop the island’s infrastructure and, in 1963, was awarded the Golden Cross medal by a grateful Greek government. His 14 page booklet was commissioned as a fund raising project by the Californian society.

********************************************************

Accursed Agios Dimitrios, known to us as Paliochora on the island of Kythira, today is still uninhabited, and in ruins. A woman’s ancient curse has come true.

Seven times in her long life, Kythira had been bereft of her children. Seven times pirates had left her like a bursting wind sack, but always-fearless pioneers reinhabited her again because the island has rich fields. As long as the pioneers were young and worked hard, they had no fear, but when luxury and old age weakened them, the cry “the pirates are coming!” became a nightmare.

For that reason, the Kythirians looked for a good hiding place, for an untaken fortress, where they could be safe and where they could make themselves invisible. Two hunters did find such a place. They told boastfully about the hidden valley, a place that nobody believed existed. They were so convincing that a group met, they found a high rocky precipice with a small, narrow entrance surrounded by higher cliffs. The old people came back with exaggerated fantasies. The dream of ages, an unfindable living place, was a reality! Nobody would ever try to find it!

Hadn’t generations lived on the island without knowing about its existence? They called the place Agios Dimitrios after their patron saint. Women and children hauled stones from the hills in the vicinity, and men built houses and churches. They used many stones to construct a high wall upon the narrow cliff top.

Freestanding, it protected the whole. Only one small entrance exited on the eastern side, no more than one meter wide, just wide enough for a donkey and one person. The wall constructed from stone and lime mortar, was more than thirty feet high and covered thirty strides from one side to the other. Behind fighting loopholes there were places for archers.

Who is he who will fight this fortress? Ram the gate? But there is no gate. Only a donkey that’s loaded can enter. Any attacker is a certain target for an archer, and the fall from the gap can take care of him.

Agios Dimitrios grew and spread all over the rock hill, like a Phrygian helmet on a warrior’s head. The little town was getting crowded and prosperous. On the staircase street there were many new houses and life was wonderful. Eight hundred people lived there with fifteen churches and twenty papades to perform weddings, baptize children, and bury the dead.

Some of the people had brought products of their fields to barter or trade. They built tables, planks upon supports, to display their extra produce. Many women and girls made the preparations for the feast. All of them took their places, poor or rich, old or young, women and men. If you were eating, there could not be a difference. There was always more than enough bread and wine because the wheat and grapes of Kythira are the best in the world. Also there was fish or lamb, sometimes even a bird or a rabbit. But these delicacies were meant for the chieftain or the notaries.

Eating, drinking, talking and laughing, and now and then singing, the joy of life had no end. Late in the afternoon they took their flutes and violins to accompany the age-old songs and dancing melodies. Warm and joyful, everyone, the young and old alike, took part because the Hellenians must dance till they can no more. This was Sunday, and the traditions of Agios Dimitrios remain as long as the sun shines.

The Kythirians feel safe and secure, because God and the Panagia protect them on their impregnable rock. There is one secret, however, about which nobody will talk. It concerns their hiding place, their cavern behind a perpendicular rock wall, the refuge for women, children, and weak people. The entrance is a rough, small opening, but low ladders lay ready for use, and behind the entrance there is a hidden backroom inside the bowels of the diamond-hard intestines of the island.

Of course, it is nonsense to assume that nobody outside of Kythira knows the richness of the island. Tales about its wealth are creeping like an oil-stain over the water in every direction, and adventurers paint their fantasy about the town, Agios Dimitrios, in the most variegated colors. These stories are reaching the countries on the other side of the Mediterranean Sea, where their horrible leader, Chair-ed-Din Barbarossa, the man with the red beard, smells prey.

One black day he and his Algerian pirates sail off in order to bring death and misery to the island of Kythira. These devils catch fifteen men from the fishermen’s village where they land and line them up in a row. “Bring me to the hidden town,” says the red-bearded leader to the first prisoner.

“No, that I don’t know…” he says, but before he finishes his answer, a big curved sword splits his brain.

“Quick, you, the following one! Where can we find your hidden town?”

“Kythira has no hidden town,” says the next man, and those are his last words.

“Enough!” roars the super-devil. “We don’t have enough time to listen to the lies of these Christian dogs! Put six of them here in a row and cut their heads off!”

Sickened with horror, the remaining prisoners see how the blood of the men of Kythira runs to the sea like a brooklet. “Now you, there, quick, tell me!” But he cannot say a word, as he has sunken to the ground that is overflowing with blood.

The question has no need of repetition because the next prisoner says, “Why should ALL of us be slaughtered? I’ll bring you where you want to go.”

Meanwhile the pirates take more frightened prisoners and these are obliged to push the heavy weapons for warfare, rolling them on their clumsy wheels. Under the whiplashes, women and children pull with ropes, yokes and halters, the cannons and, the carts along the narrow little road, over the hills, and through the hot, narrow valley, till they are almost to the point of exhaustion. On and on they go in the direction of Agios Dimitrios.

But the people of Agios Dimitrios have seen the fleet coming, and men who were seafarers in their old days know these Algerians and sound the alarm. The chieftain and his councilors do not hesitate and set everyone to work for the defense. Two strong men bring all the sick ones, the old people, and women with young children to their secret cave. Without panic, they climb above the rope ladder and through the opening into the cave. The oldest ones and the children have been of assistance, but aren’t they all children of their own land?

As the pirates come into sight with their exhausted captives, hundred are safe in their hiding place, while others stand at their posts, ready to defend themselves, their beloved and their possessions.

The red pirate is content. He has lost twelve slaves, that’s all. Some of them have been beaten to death; others have fled away. But is has gone quickly, and before sundown there is time enough to fight again in the town. He gives orders to bring the cannons in position for the attack. The cannons are primitive, but they don’t miss their target. The big iron balls destroy the barricade on the east side of the wall, creating panic among the defenders. Their leaders try to keep them actively defending. But the balls continue falling, not only upon the defending wall, but also far behind it between the houses and through the roofs.

The panic grows anew, and the attacking pirates think that theirs is an easy game. But they are wrong. The rage of the Kythirians overcomes their fear, and their hate rises over their horror. Their arrows are worth more than the muskets of the pirates.

Fighting man against man, many a pirate have been killed, throttled by the desperate Greeks. Women are looking for arrows between the falling stone blocks, and if they are attacked, they are second to none to yield, until the red-bearded tyrant furiously stirs up his devils to extreme cruelty.

“Kill them, but quick, quick! You do not fight! Get going! No pity! Quick now, quick!” And quickly it goes. The resistance is broken down and the booty prize of men is collected on the little square behind the big wall. The profit of the enterprise is small, scarcely a hundred men. The rest are half or totally dead, says an officer. It makes no sense to bring them here.

“No, but something is stinking, Achmen!” snarls the red beard. “Where are the children? The Greeks always have dens full of children. And where are the women?”

“There are not many women, commander. We have locked them up in the main church.”

“Maybe so, but it remains a stinking fact—few women and no children? Impossible! They have, of course, a hiding place somewhere. Take all your men and start seeking. Before sunset I want to be away from here because the Venetians are strong and ticklish in these waters.”

The pirates comb out the neighborhood, set fires in the growth of tangled weeds, look in the neighborhoods of the town and in the little iron mine, but do not find even a trace of people. “Nothing to find, you say,” murmurs Barbarossa, “so you cannot find them? Well, then I’ll show you how we do such a thing!” He starts talking to the first of the prisoners. “Where are your women and children?” There comes no answer and a head rolls over the soil. “You don’t want to say something, eh?” roars the furious pirate. “We’ll find out who can maintain silence the longest!”

Everyone does understand him (eternal shame for Lesbos because this evil-doer Barbarossa was born there in Greece.) “There, you! Where are your women and children?” But the answer comes from the fifth man in the second line, from big and strong , known as Mitso. He has killed seven bandits and looks horrible, covered in his own blood and that of his enemies. His voice sounds mighty. “It makes no sense, captain of the pirates, to ask these poor men for things they do not know and then cut their heads off. I’ll tell you where the women and children are! Go to that low roof over there, that is somewhat higher than our platia, and then you can see the sea. There are the women and children—people we did not need for our defense. They went in time to the mainland, and what you see here is everything that remains—us!”

“Come here, close to me, you dog!” roars the captain. Slowly, slowly, Mitso Constantinou leaves his place. People of Kythira know only one fundamental law: Better to die upright than to live on your knees, but nobody will go quickly to the place where he knows that he will be killed. He keeps his head upright and his mighty trunk, and the red beard admires him. “You’re not afraid of me?”

“I’m not afraid of the devil, consequently not of you!” says Mitso. His wounds are bleeding, but he pays not attention to them, and you can read hatred in his eyes!

The red beard grins. Such an answer he likes. And it is a pleasure to see such a sight. A mighty ringleader he’ll be. Such people Barbarossa can use very well! But the prisoner must not yet know about his future. Red beard’s cruel grin returns. “Possible that you’re not afraid, but—“and he hits Mitso in his face. “You’re lying!”

When the blow no longer resounds in Mitso’s head, he hears red beard roar once more, “You’re lying! They are hidden here in the vicinity, and you’ll tell me where they are. Do not forget that I have the means to get you talking!”

Mitso’s eyes narrow and a little muscle on his face trembles. He knows that the moment of his judgment has come. If I would be free from these ropes, and we two stood face to face and alone, then you should know what it means to call Dimitrios Constantinou a liar. With my naked hands I would kill you in the time you need for breathing three times. You with your sword and whatever—“ But inwardly a prayer forms: “Highest and mightiest Panagia, excuse my boasting; I try to save my people.”

Precisely at that moment, it happens! He hears the faint, very, very weak sound of a weeping child. Is that now the answer of the Paangia, the Mother of God? Or is that fate, destiny? Are the women and children all to be killed by these devils? That would be horrible, but he is the only one who has heard that tiny voice.

The ransacking of the soldiers makes enough noise and tumult to cover up that faint sound of that he is sure. But, what if they hear it? No, no, nobody has such ears as he has. He is sure about that. But, if they would hear it? Something must be done! He has to do something! Nobody else. He has to draw their attention, the attention of the murderers of his flesh and blood. Nothing of his considerations is readable from his set face, but do these hill-hounds see how his heart thumps? Through his head whirs his prayer: Panagia mou, my Virgin, help us! Haven’t you got some little miracle or trifle to our advantage?”

Without waiting for a sign, he turns on his heels and marches arrogantly to the pirate leader. Everything inside him is tense because he is waiting for a sabre-cut. But, instead of that, the red beard grins to one of his lieutenants; “That fellow is well suited to be a survivor!” That is exactly the assistance that Mitso needs. Instinctively, he knows now what he should do to warn the people in the cave that the whining baby is able to betray them!

He starts laughing, a deep well-contented sound, but unreal, like the lie itself. Then he lifts his heavily bound hands and starts dancing. The Algerians look surprised and do not know what to think of this ridiculous show. Should they finish that stupid nonsense, yes or no? But Mitso dances wonderfully, wildly, and they leave him alone some while, until one of the pirates asks him why he dances. “Why? Well, man, I’ve good ears. I’ve heard what your commander said. I’ve saved my life, and for that reason I’m dancing!” He hums a melody as well, and tries to sing words, but that’s too difficult. But that is necessary; it has to be done. His overstrained nerves hear the voice of the nervous baby clearer and louder. “Panagia, how frightening! What can I do? Should I shout about something? Should I yell or shriek? Scream? What? My Panagia, help me, please! I have to warn them. They have to know that the child can be heard!

Then, all of a sudden, it is there! A simple melody that the Kythirians dance very often. Something like that was already in his head with the words as well! He tries it somewhat hesitantly, and then, with more movement, comes the warning, the song of a hunter behind a hare! But instead of calling the dog to bring him the prey that he had taken, he sings: “Skotose, skiele to lago sou and etse sosse to lao sou!” (Kill, dog, your hare, and in that way save your people!) He has found the message and the way to deliver it! He goes on dancing, draws attention to himself, and adds some other phrases to avoid suspicion. The pirates look mockingly, but most of them go on with their plundering. Mitso keeps singing his song of the hunter and the hare that should keep its mouth closed.

Fear fills the inhabitants of the cave. Women and children, sick and old people, seek the farthest corners of the irregular rock floor, where they cannot see the glowing entrance eye. There is some food, but who is thinking about eating when the barking muskets, the cracking of the collapsing houses, the screaming of the wounded or dying people is so close at hand?

Sometimes dim noises can be heard, if a dead or half-dead body falls into an abyss. Two old papades pray ceaselessly in one corner. Sometimes toothless old women mumble, but mostly everyone is silent, overcome by fear from the sounds outside.

The cavern commander tries to keep his eyes on the fighting on the rock and, if nothing special is to be seen, he makes his rounds through the whole hiding place, whispering, reassuring by saying something comforting. But that’s not simple. Everyone knows that there is no possibility for consolation when any second his own people may be killed. Even if the pirates should shrink back, never yet have the pirates lost in Kythira. There is only affliction and loss for Kythirians. Loss of all the beautiful and holy things they had made during hundreds of years. How many beloved humans will be missing after this day of judgment? Everyone knows that the fight is unequal. Cannons against arrows. Well-practiced fighters against farmers and laborers. There is only one thing the people in the hiding hole can do: be quiet and wait! For that reason time creeps, trying to drive them mad.

Sometimes a child starts whining, but that is never for long. From every side you hear: “Ssssst! Soppa! The Pirates!” And that’s enough! Coughing and other sounds are subdued with “Soppa” And so it goes on. Children are softly cuddled and pampered with whispered words and everything goes reasonably well, until a sucking child starts crying, simply the weeping of a child that has to be fed in the evening time.

Quietly, but hastily, the young mother unbuttons her blouse and gives the child her breast. Some seconds later everything is quiet again and the little one sucks contentedly. A nice little happening amidst black horror.

But suddenly, the child coughs, stops drinking and starts wailing. Milk continues to seep. Everyone holds his breath in fright. From all sides can be heard “soppa, soppa!” The mother tries to make the baby silent again with her beautiful full breast, but it doesn’t work, and it seems that the little one shouts all the more. Old people shudder and whisper the name of the Panagia. Bigger children creep to the place of the young mother with her crying baby. The mother, Marika, sees them coming and meets the children’s eyes—silent eyes, but their silence seems louder than her own child’s cries. No, they don’t say anything, but they are praying and pleading for their lives with their silent eyes. They say nothing, but they pray and plead for their lives, as still more come and join them.

Marika understands that her baby may bring the pirates to their hiding place. And then, what will be their fate? And that of herself? Torture, violation by those horrible men, and death, with the coming of the devil when the horror never ends. She tries to stop the penetrating screams to dampen them with her apron, but the little one struggles loose and screams hysterically. And of course there is danger that the other children will join in. The cavern commander, now at the entrance tries to mask the opening with his body. The sounds from the outside world have lessened and the shouting has stopped. Something peculiar is going on. Are they all dead? Have they surrendered? There still is some noise, but not from fighting or defense. Plundering continues, but something different is going on.

It seems that somebody sings a dance-song, but it can hardly be heard; it is too far away. “That crying baby behind you, take care that its yelling stops,” he says to one of the old men close by.

“Quick, I have the feeling that they can hear it!” The man has hardly gone when the commander hears the words “Skotose skile to lago sou, k’etsi sosse to lao sou.”

“Panagia mou, that is the voice of big Mitso. Why does he sing such a strange song? Dog, make the hare silent: dog, kill your hare. What does he mean by that? But that must be meant for here, in the cavern. They have heard the yelling of the little one, perhaps not the pirates yet, but Mitso has, and now he warns. No, the pirates have not heard because things are quiet yet.

He leaves his observation post and hurries to Marika with her crying baby. “Marika, on the other side they can hear the infant’s screaming. Mitso Constantinou warns with his song. Now he says, “Stop the child’s crying” We are all in deadly peril. Marika, the child must keep silent. Soppa, soppa, soppa, now, little boy.” He says it hurriedly and huskily. But how will the infant hear him, when the infant’s mother cannot silence him?

“Kyra Marika,” whispers a child next to her, “Kyra Marika.” Nothing else. What more can a little child say? Marika feels the horror rising like a jellyfish in her stomach creeping up to her throat. What do they want? What do these people mean for her to do to her own flesh and blood? As she wants to protect him, she presses the little one against her breast one, two, three seconds. But then the spasmodic struggle of the little boy becomes so wild and violent that she releases him to free him. The man in front of her stretches out his hands as if he wants to take the child from his mother, so that he can do the saving murder; but how can he? “Marika, Marika, do you hear me?” But what can she answer? As if she is seeking assistance, she looks around, but she sees only eyes-eyes like glowing stalactites all around her, glimmering in the dim twilight of the cavern. Imploring eyes, piercing like daggers, like arrow points! Her skirt acts like a screen against the little beam of light at the cavern entrance, as she keeps her hand over the mouth of her son. But that is no help. No, it doesn’t do any good. When the commander goes to listen for a moment at the entrance, he hears clearly, “Skotose skile to lago sou!”

“Do you hear it, Marika? The child has to be silent, has to stop crying!” Now she herself weeps, gasps. “Save your people, Marika! That’s what Mitso says on the other side. It’s not right that we all die for one little child, Marika! And your son will perish at any rate. Marika! Marika!”

Marika tries again, but she can hardly keep the strong child quiet. She holds up the baby in front of her as if she wants to say, “Strangle him, if you can!” But nobody takes over.

On the other side of the little square under the big wall Mitsos dances and sings his silly song with the hopeless, secret warning. Over his own voice, because he has such sharp ears, he hears Marika’s child. But one more second may be fatal. “Skotose skile! Kill dog!” he roars. Behind him stand his fellow sufferers with their bound hands. Do they understand what ‘s going on?

Little Vassily is one of them who continually feels resentment, then hate. Oh yes, he thinks he understands very well why Mitso in so happy. Mitso will become the slave driver, their executioner. And he was once one of the best men of their town. A dirty traitor he is. It’s no miracle that the holy saint didn’t save the town. Indignation and hatred overcome him, and with his fingertips he touches the dagger he has hidden in his wide trousers. Oh yes, when he bends a bit, he can touch it. He comes to a decision about his duty when he touches the steel. He will do justice and punish the scoundrel who is dancing to save his own skin, ignoring horrible misfortune. It’s good that the pirates pay Vassily no attention at all!

Slowly, he brings out the big knife and frees his hands from his bonds. Now he’ll do right and punish the devil who’s dancing in spite of their horrible fate! The pirates are still unaware. He turns like a tiger on his prey. Nobody reacts, none of the prisoners and none of the pirates. Vassily closes in on Mitso, who is facing in the direction of the cavern. In an instant Vassily’s hands are aloft and plunge the knife. Mitso scarcely feels the pain, so strongly does he feel his failure to save the women and children. As his warning flows away with his life he utters a scream so that everyone, prisoners, and pirates alike, freeze in horror.

In the cavern, Marika presses her child against her body, desperately pressing until the tiny form stiffens lifelessly. Then all is silent.

The next day a group of people follows the base of the crevasse and come into the open. The last person is a young woman who is clutching a bundle. She looks strangely lifeless. But there, where the cleft makes the last turn, there where the rest of the rock town is still visible, suddenly she comes to life.

She turns and shouts with an eerie, keening voice, “never will they rebuild you, Agios Dimitrios, because all the children that will be born within your walls will die before they are as big as my son is now. Damned are you, Agios ! Be damned until nothing remains of you!”

Thus ends this legend of cursed Paliochora on the island of Kythira, today still uninhabited, and in ruinous decay.

A Note from the Editor

Paliochora, once a thriving Byzantine town on the Greek island of Kythira, was attacked, sacked, and almost destroyed by the infamous pirate, Barbarossa in 1537. Never resettled, for many years it was inaccessible, except for the hardy who hiked the dirt trails, like the one from Trifilianika. Today her ruins can be reached by car from the newly carved road outside of Aroniadika.

Some forty years ago, when engineer George Koksma and his wife Anny were sent to the island by the World Council of Churches, they rolled up their sleeves and went to work helping to develop the roads, the plumbing, and the other comforts of civilization Kythirians take for granted today—including running water, electricity, harbors and yes, even trees.

In 1963 the Greek government showed their gratitude to this industrious and enterprising Dutch couple by awarding George the prestigious Golden Cross medal. The grateful Kythirians shared, in addition to their hardships, their inimitable openhearted hospitality, their unique culture and their fascinating and often droll lore. One can imagine talks told on summer afternoons over demitasse cups of Turkish coffee and on winter evenings with glasses of fiery tsipouro and raisins evolving into sessions with Mr. Trifilis, Panayiotis Zantiotis and Dr. Iannis Fardoulis, augmented by reading Dimitri Zaglanikis’s book (whose drawings appear herein), and subsequent historical sleuthing by Dutchman Tom Lagerwey, slowly revealing Paliochora’s secrets.

Today George Koksma, in the neighborhood of ninety-four years of age, retells the harrowing tale of the tragic fate of Paliochora, sometimes know as Agios Dimitrios or Agios Nicolas. He reminds us, however, that time has been fading his memory just as surely as it has been eroding the windswept rock city that was abandoned so long ago.

As to the future, George Koksma admonishes us that, unless we become better caretakers and stewards of the heritage, we, too will contribute to Paliochora’s final destruction. Her survival or extinction as an archaeological site is in our hands.

Anastacia Conomos Condas

Summer 2000

The Tale of Paliochora was retold by George Koksma (1907-2004) and translated into English with the help of Anastacia Conomos Condas (1936-2004). A Pamphlet was produced by the Kytherian Society of California and is available for a small fee upon request by sending an email to Vikki Vrettos Fraioli

Copyright 2000

See also:

Paliochora

Special Dutch ties to Kythira from 1960 through 1971

Biography of Anne (Tasia) Conomos Condas

Paliochora on Kythera - Reconstruction