The Other side of the Coin: Return to Kythera.

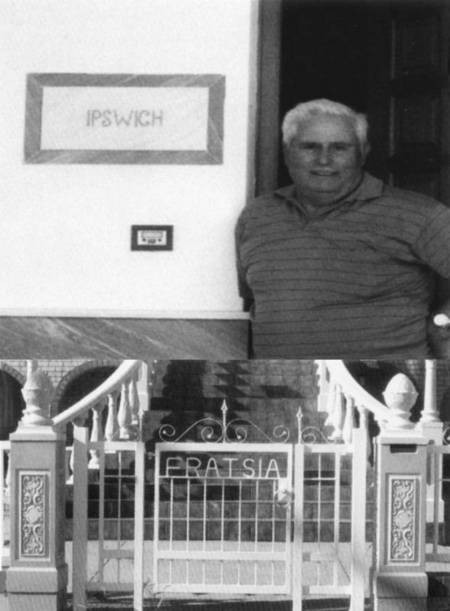

Above: Jim Pavlakis standing outside the entrance to his home in Fratsia, Kythera.

Below: The entrance to Jim's house, in Ipswich, Queensland, Australia.

Chapter Twelve. Aphrodite and the Mixed Grill.

“WHAT IMAGINATIONS MUST THOSE GREEK POETS HAVE HAD IN ORDER TO HAVE GIVEN DEATHLESS RENOWN TO THIS DESOLATE, WIND-BOUND, TREELESS, UNFREQENTED ISLAND.

VISCOUNT KIRCKWALL, 1864.

"If you’ve never heard of the Greek island of Kythera,” writes James Prineas, creator of the Kythera Family Website, “don’t worry — most Greeks don’t know where it is either. And if they have heard of it they probably don’t have anything nice to say about it.” Until I began a research project that eventually took me to this strangely haunting place, I’d never heard of it either, but I have since discovered a link between our two islands — Kythera and Australia — which is as remarkable as it is unrecognised. Although most Australians are unaware of this link, Kytherians call their homeland ‘Kangaroo Island’, and for very good reason.

Kythera’s population was 15,000 in the 1920s, but political instability and the poverty of an arid landscape caused such an exodus to the ‘land of opportunity’ that there are now only 3,000 people living on the island. There are, however, 60,000 Kytherian-born people living in Australia — that’s four times as many people as were living in Kythera in the 1920s. Prineas articulates both the link between the two islands and the state of life for most Kytherians in a recent newsletter:

It’s that time of the year again. . . the coldest, dampest, most solitary period of the Kytherian winter, when many older islanders feel like the world has deserted them. In some villages only one or two houses are inhabited, their occupants huddled close to the fire. Influenza and rheumatism is the norm rather than the exception. Many dread having to go out of the house into the permanent cloud which covers most of the island.

For those of you in Australia with heat-waves and droughts to contend with, you must think a bit of cold rain would be a pleasant change. It's easy to forget the isolation many of our relatives there are experiencing. Send them a bit of sunshine by calling them occasionally. They’ve literally kept Kythera alive so we can visit a “populated” island in the summer months, and it’s the least we can do.

The population on Kythera swells to about 20,000 in summer as expatriates fly back to visit aging relatives and enjoy the festival season. Little wonder that the Kytherians know Australia as ‘Big Kythera’. And it was the Greek café that forged this link.

Kythera is a small island to the south of the Peloponnesus. It is about 26 kilometres long and 16 kilometres wide, 282 square kilometres in all. The island’s main claim to fame is the mythological birth of Aphrodite, an event that came about when Cronus cut off his father’s genitals and threw them into the sea near the coast of Kythera. The severed genitals caused the sea to foam and the foam produced the beautiful goddess. Zephyrus blew upon Aphrodite, who came ashore in a giant scallop shell near the village of Paleopolis. It was also on the island of Kythera that Helen of Troy met with Paris. In addition to this wild, mythical, and romantic past, shaded terrace cafés, picturesque harbours, springs hidden in secluded, mossy grottoes, and some of the warmest people you will ever meet are part of the island’s appeal. But the desolation of Kythera’s mountainous landscape overshadows the visitor’s first impressions.

Kythera is a barren, rocky island that rises sharply from the sea and has few natural resources. Perhaps this is because the wind, which blows you across the tarmac and into the airport, and makes the powerlines sing on the island’s higher vantage points, has blown the topsoil into the deep blue Ionian Sea. At the beginning of the 20th century, olive groves and a few fertile valleys terraced with fruit and vegetable gardens barely supplied the needs of the population. Peasant farmers raised small crops of wheat, legumes, grapes, almonds, and olives, kept a few goats, and produced home-made wine and olive oil, but most were acutely poor. Others searched for work on the mainland, leaving women and children struggling to put food on the table. Some exported olives, honey, figs, and wine to the mainland, but there was no opportunity to accumulate wealth. To make matters worse, this hand-to-mouth existence was lived in the shadow of the continual threat of war.

But to drive the roads scratched across the surface of this empty landscape, past decaying rock walls and tangles of thorny bushes and prickly pear, through silent villages with empty streets and crumbling stone houses, is to understand that Kythera has been eroded in other ways. Mass migration to Australia and other parts of the world has devastated the island. Fields arc neglected, clothing, diaries, and furniture are entombed in derelict dwellings, and decaying villages, deserted of young people or abandoned altogether, have virtually become ‘ghost towns . As Alexakis and Janiszewski explain, “The principal legacy of unbridled depopulation is a landscape inhabited mostly by elderly residents, and peppered with disintegrating villages, unkempt roads, unploughcd fields, collapsed windmills, and ahandoned homes, schools and churches.”

Greek cafés were certainly the means by which desperate people gave their children a better life, but in her unforgettable photographs of villages like Fratsia, Mitata, and Trifyllianika, Alexakis documents the devastation that represents the other side of the coin: an evening purse that rots on a wall hook, a warped family photograph that fades into dust, a petrified shoe that lies amongst the rubble, a torn letter that rests beside a postcard from Australia. This is the debris of abandoned lives. Prineas, whose family comes from the island, foresees in this devastation an even more tragic consequence — the demise of the simple Kytherian lifestyle.

In 1900, Aphrodite’s birthplace overflowed with inhabitants; 14,000 people lived in 60 bustling villages dotted across the island. The population swelled to about 15,000 in the 20's. But as the shock waves of Athanasios Comino’s first Greek fish shop in Sydney began to be felt on the other side of the world, Kytherians followed a pattern of chain migration that took most of the male population to Australia, and by the 1940's villages were emptying. It was as if someone had pulled a plug that drained Kythera of fathers, brothers, and eligible bachelors. Most emigrants intended to send money home while they worked toward the day when they could come back as wealthy men to care for their families. But few returned. Sometimes families joined them in Australia. Sometimes they returned briefly to find a bride. The Greek shopkeeping family, a singularly Australian phenomenon that contributed so much to the culture of a young nation, is a wonderful story, but Australia’s Greek café has its upside. And this is played out in the villages of Kythera, where elderly people are the main inhabitants.

There is a monument in Kythera that marks the place where tears were shed for loved ones who left for the other side of the world, loved ones who mostly didn’t come back. Above Potamos, the port from which boats departed for Piraeus and, eventually, Australia, a plain, rectangular block rests atop a low, circular platform trimmed with blue paint and edged with a simple scallop design formed in curved metal rods. Some locals call it the ‘Crying Stone’. The inscription reads:

The Place of Tears ofJoy and Grief for those who came and went, in the year 1908.

Erected in the memory of George and Cleopatra Khlentzos.

Historian, Hugh Gilchrist, describes it as “a memorial to those who went down the bill to the ships, and those who would never return.

Because of the process of chain migration, many of the men who had cafés in Ipswich came from one village in Kythera, the village of Fratsia. While Ithacans appear to have opened the earliest Greek shops in Ipswich, it was the Kytherians whose businesses endured. Harry, Charles, and Jim Londy left Fratsia in the second decade of the 20th century. They operated shops in several towns, at least three in Ipswich, and Harry went on to build one of the most successful and best-remembered café businesses in that city. The story of the Londy family typifies the way whole families left their homeland behind and the way families cooperated to establish themselves in Australia through their cafés.

Harry Leondarakis migrated to Australia at a young age under the guardianship of his uncle, Harry Andronicus, in Toowoomba. He was soon joined by his twelve-year-old brother, Charley, and his brother-in-law, Jim Leondarakis. Harry and Jim had the Paragon Café in Dalby before moving to Rockhampton. When he left school. Charley worked for a proprietor who had recently to introduce the latest milk bar products from Sydney, so he learned to make ice-cream, ice-cream sodas, malted milk shakes, sundaes, and parfaits. In about 1920, Harry and Jim bought the Sydney Café near the railway station in Ipswich and Charley joined them as a full partner. The three traded under the name ‘Londy Bros.’ because Pennys, Woollies, and Fosseys were successful business names at the time and ‘Londys’ had a similar sound. Soon afterwards, the partners adopted ‘Londy’ as their family name.

In the early 1920’s, Londy Bros opened the Café Australia in Ipswich and the American Bar in Gympie, which was managed by their sister, Arete, and her husband. Harry then established Londy Brothers Paris Café in Ipswich with Jim’s son, Mick. Charley opened Londy Brothers Blue Bird Café in Bundaberg with another brother-in-law, Mick Levonis. Jim moved the Capitol Café and the Paragon Café in Toowoomba. When Jim died, his wife, Rene, set up Londy’s Café in Texas, and later moved to Townsville, where she started another Londy’s Café in partnership with another relative. Mick and Calliope Levoms moved on to Londy Brothers Café Mimosa in Maryborough and their sons bought out the Capitol Café in Toowoomba. The Londy family eventually went into the Theatre business on the Redcliffe Peninsula.

In the wake of the Londy family’s departure for Australia, the Londy home in Fratsia is abandoned and dilapidated. Stalks of grass sprawl into the open doorway, the tiled floor disappears here and there under layers of grit the wind has blown in, the black, skeletal remains of a light fitting perch on the pine table, and the chairs, which seem to wait bravely for the inhabitants to return, are weathered and broken. In the eerie silence, as the wind blows across the desolate landscape and in through the unglazed window, one can almost hear voices bringing news of a land of promise, and as the afternoon sun slides across the furniture and onto the cloud-like faded blue wash on the crumbling walls, it is not hard to imagine the silent tears of the women as they prepare the farewell meal. Those who lived to see their grandchildren grow up in their adopted homeland still carry the land of their fathers in their hearts. Speaking of the Greek migrants who eventually carved out a new life in Australia, Conomos, also a Kytherian, observes that “even 50 or 60 years of life in Australia could not make them forget the rock from which they were hewn.” Those memories eventually called some migrants back. Not surprisingly, a number of café proprietors have remigrated. Jim Pavlakis is one of them. After owning a café in Ipswich for more than 20 years, Jim returned to Kythera to spend his later years amongst the homes of his ancestors. Like so many other proprietors in Ipswich, Jim was born in Fratsia and followed members of his family to Australia.

Jim’s sister, Maria, brought him to Ipswich, where her husband was a partner in the Kentrotis brothers’ Regal Café. After working for some time at the Regal, Jim bought Tony’s Café after the proprietor, Tony Veneris, was murdered in 1962. The shop was submerged for five days beneath floodwaters in 1974, but otherwise Jim’s business flourished. He made good food, his customers liked him, and his shop was the hub of Ipswich’s youth car culture. During the 1980s, Jim built a house near the city centre. It is much like any other two-story brick Queenslander except that the wide front steps and deep verandah are covered with tiles and edged with an impressive white concrete balustrade. The house encapsulates the history of Greek immigrants who have embraced Australian culture but manage to imprint it with something of their earlier identity. For those who know about the Greek café phenomenon, however, the seven letters welded into the front gate tell the whole story. Jim called his Queensland home FRATSIA.

Unfortunately, not long after work on the house began, Jim suffered some health problems and over a period of years decided to return to Kythera. That was nearly 20 years ago. Jim became mayor of Fratsia and is still active in the community there. He is even restoring some of his family’s homes, or at least trying to prevent further deterioration. The houses in Fratsia are mostly two-storey rectangular buildings with wide arches on the bottom level, a strong construction method that accounts for the fact that so many still survive. They are made of stone and plastered with concrete. There is not a verandah in sight. Jim feels a strong attachment to Ipswich and is grateful for the opportunities it brought into his life, but when I ask him why he returned to Kythera, he explains, “Well I just did not want to die in Australia, you understand.” When I visited Jim, his lovely wife, Lumbrini, and their gang of feline hangers-on, I stayed with them in their home.

I follow Jim across the silent street to the house he has restored. A black iron gate swings open and I step onto the tiles of the front patio. On the concrete wall beside the front door, seven letters are written in gold and framed with marble — IPSWICH.

TO ORDER a copy of Aphrodite and the Mixed Grill:

Phone: (07) 3281 1525 or

0439 664 291

Enquiries:

Contact Toni Risson by email here

Or, send, name, address and cheque/money order to

Toni Risson

130 Woodend Road

Woodend, 4305.

$49.50 (incl. GST)

Plus $11 (Postage and handling).

Composite Front-Back Cover as a .pdf

Aphrodite coverV1.pdf