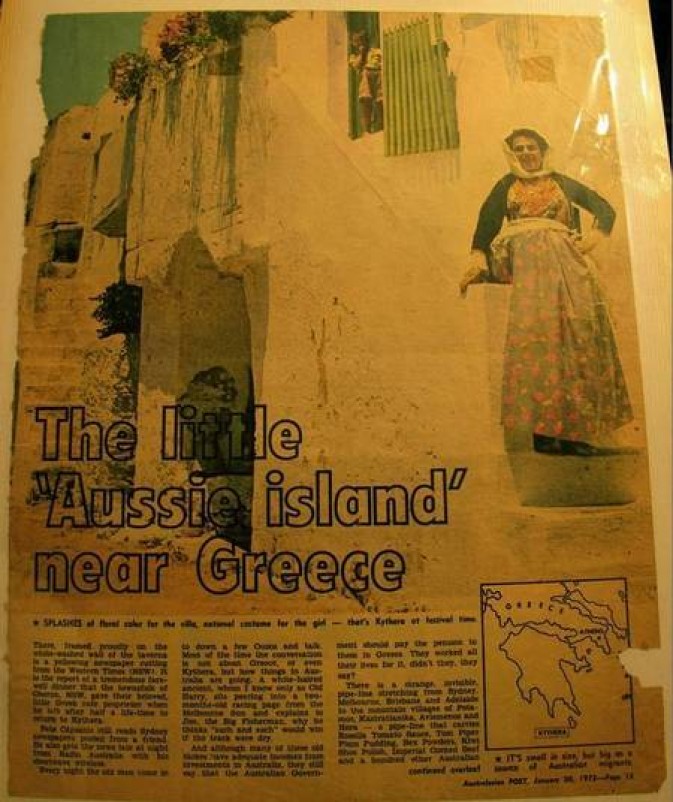

The little Aussie island near Greece - Australasian POST, January 20, 1972

Page 15

From the photo album of Alex Morelli

Santa Barbara, CA

Australasian Post. January 20, 1972. pp's: 14-16.

Post in the Aegean.

From Geoffrey Kenihon

For 100 years or more the people of Kythera have done their best to populate Australia. Eight miles across a sparkling blue channel from the Greek Peloponnese mainland, a rugged green island rises steeply from the Aegean Sea. It is Kythera, sometimes called the “ghost island” of Greece, because of its deserted forms and villages, where open doors creak in the wind at the entrance, to empty, silent homes.

It seems an unlikely place to find characters so Australian in speech and manner that they seem to have stepped from the pages of They’re A Weird Mob. But they’re here in abundance.

The reason Is that just about every second man among Kythera’s present population of 3500 can look back on at least some part of his life spent in Australia, working hard and making enough money to return to the island of his birth.

There are other reasons why Kythera’s inhabitants jokingly claim to be the ‘seventh State” of Australia.

The islanders claim that the first Greek migrants to Australia in the 1860s came from Kythera, establishing a tradition which subsequent generations have followed.

The flow became a torrent in the years after World War II (there are now more than 20,000 Kytherian migrants and their children in New South Wales alone with a consequent shrinking of the island’s population.

Today Kythera, the ancient island of Greek mythology where Aphrodite. goddess of love, rose from the sea, is mostly a place of old men sitting in the sun outside their local tavernas, reminiscing about the razor gangs in The Rocks, or the depression years on the road to Gundagai.

There are tough, little, stubbly cheeked, bright-eyed men like Pete Capsanis who runs a taverna here in the coastal village of Aghia Pelagia. When I first went in to taste the local “krasi” rot-gut, and addressed him in my halting Greek, Pete interrupted with: “Cripes, mate, speak English, will you. I need the practice.”

There, framed proudly on the white-washed wall of the taverna Is a yellowing newspaper cutting from the Western Times (NSW). It Is the report of a tremendous farewell dinner that the townsfolk of Oberon, NSW, gave their beloved, little Greek cafe proprietor when he left after half a life-time to return to Kythera.

Pete Capsanis still reads Sydney newspapers posted from a friend. He also gets the news late at night from Radio Australia with his shortwave wireless.

Every night the old men come in to down a few Ouzos and talk. Most of the time the conversation is not . about Greece, or even Kythera, but how things in Australia are going. A white-haired ancient, whom I know only as Old Harry, sits peering into a two-months-old racing page from the Melbourne Sun and explains to Jim, the big Fisherman, why he thinks “such and such” would win if the track were dry.

And although many of these old blokes have adequate incomes from investments in Australia, they still say that the Australian Government should pay the pension to them in Greece. They worked all their lives for it, didn’t they, they say?

There is a strange, invisible, pipe-line stretching from Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide to the mountain villages of Potamos, Kastratianika, Avlemenos and Hora — a pipe-line that carries Rosella Tomato Sauce, Tom Piper Plum Pudding, Bex Powders, Kiwi Shoe Polish, Imperial Corned Beef and a hundred other Australian products you will find nowhere else In Europe.

It Is hard to find one house In Kythera’s 60 semi-deserted villages that does not have at least one family connection with Australia. So much so, that the post master keeps a big book, and every air mail letter that arrives on Kytbera with an Australian stamp on it must be signed for like a registered letter. It Is just automatically assumed that a letter from Australia has money tucked inside.

And that is so right. On Sunday, market day in the main village of Potamos, the local branch of the National Bank of Greece takes almost as many Australian $5 and $10 notes across the counter as It does Greek drachma currency.

Right now, Kythera, which the Greek Government considers as one of the most remote and primitive of the nation’s 600 islands and a handy place for exiling communists and other political bad boys, is about to open its doors.

Onassis, the shipping and Olympic Airways magnate, is building an aerodrome below the beautiful Aghia Moni Byzantine monastery, gleaming white on its brooding mountain. And the Kytherians do not look at the landing field as a gateway to the bright lights of Athens or a short-cut to the 15-hour, once-a-week boat trip to Piraeus. “Now we’ll be able to fly direct from Kythera to Sydney,” they say.

There is talk of raising money for a modern, tourist hotel on the promontory opposite where my wife Kerry and I live at Aghia Pelagia with its breathtaking view of the Peloponnese across the channel.

And apart from its natural beauty, the island has much to offer tourism. There are more than

1000 churches mostly Byzantine — on Kythera, and ruins that tell a story of past greatness.

The Venetians conquered Kythera in the 12th century and the ruins of a huge fortress still guard the entrance to Kapsali, a tiny, picture postcard harbor at the south end of the island.

Then, In 1811, Great Britain wrested Kythera and seven other Ionian Islands from Venice and a

new 50-year era of prosperity came to the island.

“The British were the only mob to ever do a damn thing for this place,” an old man will tell you in the village of Friligianika. And he talks with pride of the roads, the bridges, the schools and court houses that the English left behind them when they gave their island colonies back to the new, independent Greek Government In 1864 after the Greeks had thrown off the centuries-old Turkish yoke.

The Kytherians were of course British subjects in those days; today, scores of Kytherian - born people who worked in Australia for most of their lives before returning to their island home, hold Australian citizenship and passports.

They always say they are going back to Australia — soon. But Kythera has the Mediterranean philosophy of “manana” — or, in Greek, “avrio” —- so that their Australian holioay, like tomorrow, never comes. Life drifts lazily by, the sun shines from a cloudless, blue sky for more than 300 days of each year and living is slow and easy.

It was at the time when Britain ceded Kythera back to Greece that the first Kytherian migrated to Australia. Now, more than 100 years later, no one can really tell with certainty who that first Greek migrant was — there are many claims by several Kytherian families — but everyone is emphatic that Kythera provided the first Greek migrant to Australia.

Whoever he was, he did so well that it wasn’t long before brothers, cousins and friends were also setting out for the new land of opportunity and the first pocket-handkerchief farms were left deserted and fallow.

Years later, as the first of the new, rich and successful Kytherians came back to their villages, they brought with them more than wealth, a new language and acquired Australian tastes and mannerisms.

They brought trees —strange, new trees unlike any that grew around the lands of the Mediterranean Sea.

The new trees have grown tall, and as you approach the largest village, Potamos, you could be excused for thinking that you are about to come upon a small Australian township. The road is lined with stately blue gums and by the winding, mountain road that leads from Aghia Pelagia up the steep escarpment, the wattle blooms in the spring.

It is In Potamos that you will find handsome, 59-year-old Zachariah (“call me Roy”) Menagas, who played a part In the Australian film classic, “Forty Thousand Horsemen,” mixed a mean cocktail in many of Sydney’s pre-war hotel lounges, cut ladies’ hair and played his saxophone in Brisbane dance bands, before he retired back to the family villa on Kythera a decade ago.

Roy is taking a trip back to Australia next year — he thinks.

Kerry and I, and Nick the doctor, Jim the Big Fisherman, and Stratis, the shop-keeper who dances like Zorba The Greek, held a great party at Roy’s pad the other night. Costa, the English-speaking cop was there with his missus, and so was Sophlos, the master photographer who has won prizes In photographic exhibitions all around the world.

Roy whipped up some Brandy Alexanders for the girls while the rest of us sat around and drank from cans of Fosters which reached this island outpost by means known only to the mystery men who operate the International “pipeline.”

We danced go-go and Zorba, and Roy cut as mean a rug with Kerry as he’s done since he was a “muso” In Sydney 25 years ago. We sang Greek folk songs, and Waltzing Matilda, and dawn was breaking over the peak of Aghia Moni before we wended our way through the silent, cobble-stoned streets before driving down the mountain. It was like coming back from any allnighter in the bush. “You know, Kes,” I mumbled, as the headlights picked up the first whitewashed cottages in our little village. "We never left home.”