Ed Saltis. Winner of the Sydney to Hobart Ocean Race. 1998. Ten year anniversary. 2008.

Eye of the storm

The Sydney Magzine. Issue 68, December 2008, pp. 42-51

Ten years after the most tragic events in the Sydney to Hobart’s history, the iconic race has moved on, writes Malcolm Knox

From a distance, the start of the

Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race looks as picturesque as a painters tableau, silent and graceful. Up close, it feels more like a rugby maul. There is yelling, sledging and sometimes a collision. Partly it is the combat of each yacht timing its run across the starting line; partly it is the congestion of more than 100 boats in Sydney Harbour.

The start of the 1998 race was typical. Barely had the starting gun tired at 1pm on Boxing Day than the 115-boat fleet’s biggest yacht, the 83-foot Nokia, crashed into two competitors less than halt its size:

Sword of Orion and Bright Morning Star. Accusations were shouted and red and yellow protest flags went up. The only boat ot the three to suffer moderate damage was Sword of Orion.

She was one of the best-crewed yachts in the race. Owned by Rob Kothe, she had as principal helmsman Admiral’s Cup sailor Steve Kulmar, a highly experienced yachtsman from Sydney’s northern beaches who’d sailed 16 Hobarts and five Fastnet races. Kothe and Kulmar had met for the first time that September, and Kothe had impressed the sailor with his professionalism. They started to put together an 11-strong crew that included an Englishman, Glyn Charles, 33, who had sailed in the Olympic Games and Admiral’s Cup as well as countless top-flight offsnore races; and a full-time sailing master, the “manager” of the boat, Sydney sailor Darren Senogles.

Among the crew was 24-year-old Sam Hunt, a junior member eager to learn. The professional ethic with which the Sword of Orion crew approached the race was typical of an era when the Hobart race was transforming from a “Corinthian” or amateur event into a professionalised, big-business one. Hunt embraced this fully, having wanted since he was a child to work his way into the elite ranks of offshore sailors who are known by skippers around the world and drawn on for crewing in the big "category one" races, such as the Fastnet off England, the big-budget racing off Newport, Rhode Island and Bermuda, and the Sydney to Hobart. Largely due to the rigours of the Hobart race, Australian offshore sailors are held in high esteem.

Sydney to Hobart sailors are generally versatile, able to squeeze into small boats of about 33 feet in

crews of six, or man maxis with crews of three times that, in more comfortable cabin conditions. But for the serious sailors, the three, four or five days it usually takes to sail the 1170 kilometres to Hobart are all about pushing themselves through sleep deprivation, seasickness and any number of unforeseen emergencies to race their boats quickly and safely.

Once Kothe and Kulmar had put their team together, they won the Hamilton Island regatta, a major lead-up to the race. Hunt remembers their serious team spirit mixed with family feeling. The day before the race, Kulmar and his wife, Libby, entertained crew and family at their Manly home.

Like the rest of the fleet, Sword of Orion’s crew had heard ominous if imprecise news from the pre-race weather briefing. Forecaster Ken Batt, from the Bureau of Meteorology, told the skippers there was a storm brewing further south, but due to the complex way in which different weather systems were converging, the three main models used for forecasts were in conflict. It was impossible, Batt said on the eve of the race, to know precisely how severe the storm would be. That there would be a storm was not in doubt; the only question mark was around its strength.

Once they turned out of the Heads, the crews were on a high. The 115-strong fleet tore down the east coast in the first 24 hours so fast that the leaders, Brindabella and Sayonara, were several hours ahead of race record time. The fleet was past Eden in a day — by comparison, in the tough 1984 race, the fleet had taken four days to get past the south-coast town.

The joy of high-speed racing was tempered, however, by the knowledge that the forces pulling the fleet south were connected to opposite forces awaiting them. The clockwise-spinning low pressure system forming up of the edge of Bass Strait was, like a spiral, perfectly balanced: the leg that was slinging the fleet south would soon be met by the rotation of the system pushing up the other way.

The first yacht to retire from the 1998 race was ABN Amro Challenge, skippered by former world champion lain Murray and navigated by Adrienne Cahalan, the Sydney yachtswoman who had achieved almost everything in world sailing, from 18-footers on Sydney Harbour up to Whitbread Round the World flyers. As a navigator, Cahalan was, and is, right at the cutting edge of weather forecasting technology and interpretation.

“It’s hard to imagine from today’s perspective, but we had no internet on board, none of the instant computerised information that we rely on now,” she says. “Instead, we had paper charts and a VHF radio with a fax machine pumping out weather faxes.” Not all boats had barometers.

In 1998, ABN Amro Challenge didn’t make it as far as the storm that was building down south. They were sailing near Batemans Bay late on the afternoon of the 26th when Cahalan had just picked up a weather fax, which showed the low developing in Bass Strait.

‘I was looking at it with lain, and we were saying there wasn’t much space between those isobars — it looked severe. We were flying south under a 30-knot northerly, and then, bang, the rudder sheared off.”

The jolt nearly tossed Cahalan overboard through the lifelines:

“We had to turn in to Batemans Bay and were the first boat ashore.”

Cahalan was fully aware, however, of what was developing. “Bass Strait is very shallow, and when the seas are big and the wind is blowing strong against the direction of the current, the waves can stand up and break like waves on a beach. By comparison, you can have 85-knot winds in the Atlantic Ocean and be reasonably comfortable because it’s deep water and all the waves are the same height coming from the same direction and not breaking. Boats that had retired and wanted to sail away from the worst of it sailed north, which meant getting beam-on [side-on] to the waves, which increased the chance of the boat being rolled.”

Meanwhile, during the night of the 26th and the morning of the 27th the fleet was flying. Even the older wooden yachts were well ahead of where they would usually be, and Ian Kiernan, the founder of Clean Up Australia and a veteran of a dozen Hobart’s, was aboard his vintage 37-footer, Canon Maris. Twenty-four hours into the race, Kiernan believes his boat was running second on handicap. Also up there was Winston Churchill, Richard Winning’s wooden veteran, which had been an entrant in the very first Hobart race 53 years before. There was a special affinity between Canon Maris and Winston Churchill, Kiernan recalls.

“They were treasured mates of ours, and embodied the qualities of mateship and helping each other that are the best things about this sport,” he says. “We were going like hammer and tongs to beat each other, as we would with any other boat, but it was always fair and tough competition.” As fair as it could be, of course, when father and son race against each other: on Kiernan’s boat was Jonathan Gibson, the son of John Gibson, a crewman on Winston Churchill who’d soon be involved in one of the most dramatic and tragic battles within the battle.

On a hunch, Kiernan had put some improved safety equipment on Canon Maris before the race; yet he had also lightened its weight, taking some equipment off. “I blame myself for what happened,” he says now. “I’d always carried a system of heavy line on the boat which would control the way the boat surfs when it’s going down a wave. We were lighter that year, and not getting that control. It’s fair to say that I always carry that heavier weight now.”

The turning point came with a ferocious suddenness on the race’s second afternoon. As it entered the funnel-like Bass Strait —known as “the paddock” — the fleet was met by winds from the south-west not only at the forecast 40 to 50 knots, but gusting to almost twice that strength. The sea’s surface was whipped white.

At 2pm on December 27, the boats did their “sked”, the twice-daily call-in. In a sked, the radio operator would ask each yacht for its position. It was forbidden for the yachts to give any more information — reporting weather conditions or anything else might give a competitive advantage to other yachts. But on Sword of Orion, Rob Kothe saw fit to break the rule, and for good reason: he reported that his crew was being mauled by winds gusting up to 78 knots.

The bombshell was registered by the entire fleet, all of whom were in severe winds and seas of up to 20 metres by then.

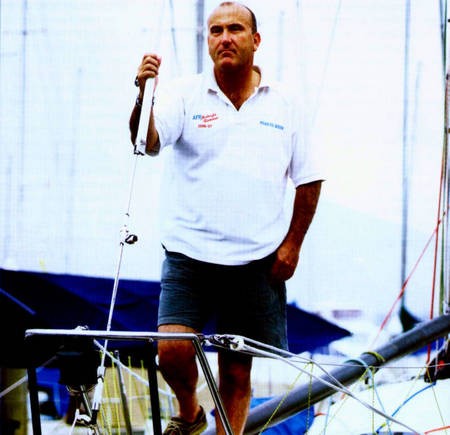

Ed Psaltis was skippering AFR Midnight Rambler, a 35-foot sloop he and Bob Thomas had bought only four weeks earlier. Psaltis was a second-generation Sydney to Hobart veteran; his father Bill was one of the best-known members of the sailing fraternity.

APR Midnight Rambler had been sucked into Bass Strait by the force of the cyclone with the rest of the fleet and was just off Gabo Island at the 2pm sked* (*slanguage for schedule(?) on December 27.

“When we heard Sword of Orion give the wind speed,” Psaltis says, “someone aboard said, ‘Hey, they’re not meant to do that.’ But I realised immediately that it was necessary for safety.”

AFR Midnight Rambler was close to both Sword of Orion and Winston Churchill, and bore the brunt of the storm. Being further southwest than much of the fleet, Psaltis decided to aim “high” into the wind, that is, in more of a southerly direction than most of the fleet, who were tempted to ease off towards New Zealand.

“It was a decision based purely on the direction of the waves coming at us,” Psaltis says. “If we’d headed away from the waves, we would have been beam-on and might have rolled. So we tried to attack the waves more directly. It wasn’t a racing decision; we weren’t racing, we were surviving. If our chances of surviving had been improved by turning around and heading north, we’d have done that.”

Having raced ahead of schedule into Bass Strait, the smaller boats were being pounded the worst. By 3pm rain was driving in like horizontal needles flung by the wind. On Canon Maris, Kiernan had had enough.

“I was off watch at the time and came up on deck,” he recalls. We were cascading down off huge waves in different directions. I said to [then the most experienced Hobart racer and navigator] Dick Hammond, ‘We’re going to roll this boat tonight.’ As a skipper, you have a huge responsibility to the people on board, and to the boat itself. I felt that even if we survived the night, we’d probably do great damage to this boat. So I said we should pull out. Dick growled, ‘Well, Ian, I agree.’"

One incident over the radio “put a dagger of icy fear in me”, Kiernan says: a mayday call from the Winston Churchill. “They were our mates, and we believed that they might all have been lost. Three of them died.” Jonathan Gibson, the member of Kiernan’s crew whose father was on Winston Churchill, would sail back to land and wait for several more hours, not knowing if his father was alive, before learning that he’d reached safety.

On Sword of Orion, the competitive drive, as strong as it was, also had to bow to nature. The crew had been fairly confident of racing on until about 3pm when wind gusts of an extraordinary 92 knots hit them and the irregular angles of the breaking waves, on average 12 metres high but up to 20 metres, put the yacht in constant danger of being rolled. When the barometer was down to 982 kpa — a massive drop in just a few hours — it flew off the wall with the force of a wave and smashed; Kothe and Kulmar decided it was time to retire from the race.

“It was a tough decision and a few of the guys were disappointed,” Hunt recalls. “It’s bad when you think of the time and effort you’ve all put in. But it’s the owner and skipper who make these decisions.”

The boom was lashed to the deck and the boat jibed ahead of the wind, not aiming for land so much as trying for the safest way to get out of the exploding low pressure system. Darren Senogles and Glyn Charles stayed on deck while the others went below to rest.

“I was lying on the middle of the floor sleeping on some sails,” Hunt says. Suddenly, at about 4pm, he was woken when everything went black and the boat was being pitched sideways down a massive wave. Then it rolled. The force of the capsizing motion bent the mast and wrapped it around the starboard side of the boat. After a few seconds the hull righted itself, but the crew below decks had been flung about like rag dolls, some sustaining minor injuries. Immediately, Hunt heard the sickening cry from above: “Man overboard.”

When the boat righted itself, Senogles discovered that Charles’ harness had broken and the Englishman was in the water with the boat drifting away from him in the wind and swell. Senogles told leading sailing writer Rob Mundle in his book Fatal Storm that he saw Charles try to swim a few strokes, labouring with an obvious injury, before losing sight of him.

“It’s self-explanatory what happened,” says Hunt, still emotional about the death of Charles. Senogles has found it hard to talk about the day, and politely declined the Sydney Magazine’s request for an interview.

After drifting on the sea for several hours more, Sword of Orion was located by a navy helicopter, and most of the surviving crew were winched up by a rescue team in the middle of the night while others stayed on board to get the boat to land. Glyn Charles’ body was never found.

There was mayhem in Bass Strait, with emergency services being swamped by calls and the navy called in. Winston Churchill had been abandoned. Three of its crew, Mike Bannister, Jim Lawler and John Dean, died during the night of the 27th when their life raft was rolled by a giant wave. John Gibson and John Stanley were the only two occupants of the raft to survive. On Business Post Naiad, one of the toughest handicappers in the race, skipper Bruce Guy died of a heart attack on board the boat and a crewman, Phil Skeggs, died on board from injuries sustained when the boat rolled. On the mid-fleet yachts there had been capsizes and rescues. In the space of a night, the fleet was decimated by nearly two-thirds.

Even for those boats that finished the race, the survival imperative overrode the racing instinct. AFR Midnight Rambler came through the terrible night of the 27th and progressed south. By the time Psaltis and his crew were alongside Tasmania, we had a lot of water down below, we were baling out constantly, we had no radio, no GPS, and were using only the compass to steer”.

Psaltis felt they were in a good position competitively, but it wasn’t until the high-frequency radio started working again off Bicheno that he realised the race had paled into insignificance.

“That was when we heard on ABC Radio that other boats had rolled, Winston Churchill had sunk and nine men were missing on its life rafts.”

Psaltis and his crew crossed the finishing line on the Derwent at dawn on December 30, tenth across the line and the winner of the race on handicap, the smallest yacht to win in a decade. Only 44 of the 115 starters got to Hobart; 24 boats were abandoned or later written off and 55 sailors were rescued. It was, says Psaltis, “the pinnacle of my career, a fantastic feeling, but mixed with terrible sadness. Jim Lawler had been a good friend of my father. When we were in Hobart, my father told me that Jim had died in the water. It was a tough conversation.”

Before 1998, in 53 years of the race, more than 35,000 sailors had contested the Sydney to Hobart. Only two had ever died from injuries sustained during the event and none had been lost overboard. The old saying about the race — wooden boats and iron men” — was confirmed by the 1998 event and enhanced by the heroics of the rescuers.

Nevertheless, changes were necessary, and 10 years on, this year’s race will carry the legacy of the 1998 event. The Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) held its own investigation, and combined its findings with the recommendations made by the NSW Coroner, John Abernethy, to reform the race.

Matt Allen, now the commodore of the CYCA and a sailor in 20 Sydney to Hobart races, summarises the new requirements:

“Fifty percent of each crew must have done the Safety at Sea course, a theoretical and practical course involving life rafts and other safety equipment and what to do during aerial rescues. Two crew must have first-aid training. Half the crew must have completed a category one ocean race, and all must be 18 years old or over. Before the start, all skippers must attend the 8 am weather briefing. There is a lot more compulsory safety equipment, such as personal EPIRBs [Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons], personal strobes, and approved life vests. All yachts must carry a barometer.

“On Sydney Harbour before the race, all yachts must go past the starter with their storm sails up, to show they’re in working order. Then, during the race, all yachts must report their condition when they pass Green Cape and enter Bass Strait — just to give them pause to think and consider whether they’re ready for the rigours of the crossing.”

And then there is the “Sword of Orion” rule; “When winds are above 40 knots, it is mandatory for the boat to report those winds.”

These requirements have a financial cost, as well as changing the underlying character of the race. As Vanessa Dudley, a former world champion who is also editor of Australian Yachting magazine, says; “The overall experience has changed. The Hobart used to be the race that just came around at Christmas time, but now it’s a much bigger deal.

“There are a lot more full-time professional sailors and crews involved, and the cost of racing has gone up a lot. That’s the case with the sport generally, but the Hobart always used to be a very accessible race for ordinary club boats, unsponsored, with amateur sailors. It would be a shame it the race became inaccessible for dinghy sailors, like I was when I started.”

For all the skippers in the Sydney to Hobart race, preparation are now on more of a professional footing, whether they are full-time pros or not. They assemble their crews earlier, do more racing together day and night, improve their personal fitness, prepare their on-board weight carefully, and test out their boats as rigorously as possible.

Although the past few years have been relatively calm, every Hobart race is an endurance event by its nature and all sailors know that any given year could be another 1998.

But Matt Allen says the amateur spirit hasn’t been drained from the event.

“Love and War won the race on handicap two years ago, with an amateur crew and a 33-year-old boat. Of course it costs a lot to put together a line honours contender like Wild Oats XI, but you can still compete at any level. Yes, there used to be more crews that were dad and his sons and a few mates, but people take it more seriously now in a lot of respects, and that’s not a bad thing.”

In this year’s race, weather forecasting information available on the yachts makes 1998 seem like generations ago — which, in yachting terms, it is. Adrienne Cahalan will be navigating on one of the line honours favourites, Wild Oats XI. This will be her 17th Sydney to Hobart race.

Psaltis will be skippering another APR Midnight Rambler, the fourth yacht he has raced under that name. Kiernan will be sailing Canon Maris again, for the first time in the Hobart race since 1998. The reason he hasn’t done the race since then, he says, “apart from the fact that my family didn’t want me to do it again after that race”, is the need for a generous sponsor. This year, with Sanyo, he has managed that, and is racing again in a crew of six.

Hunt, now 34, achieved his dream of becoming a full-time sailor with a high reputation in all positions around the boat. Having spent most of his career doing the daredevil work on the bow, he has graduated towards the leadership positions on and around the helm. This year he will be on the brand-new 63-foot entrant Limit. But little, he says, was left to chance on Sword of Orion in 1998. Like other boats that got into trouble and lost sailors, it had one of the toughest and most gifted offshore racing crews. Yet so traumatic was that year that three of its crew decided not to race the Hobart again.

Not Hunt. “In 1999, Rob Kothe bought a new boat and called it Sword of Orion, giving it the same paint job as the old boat. Some of the guys had their doubts about that, but we went in the Hamilton Island regatta that year and raced together as a group. That was how we closed it all off.

‘A lot of good things have come out of ‘98. Ever since I was a kid, this race was one of the biggest things I could ever do in sailing. It still is. I’ve done the Fastnet and other ocean races overseas, but none of them is quite as big a test as the Hobart. And since ‘98, people have learnt to watch theip safety all the time, down to the smallest detail. It’s safety first, all the time.”